We Must Never Forget

Remembering the 80th Anniversary of D-Day

"Never was so much owed by so many to so few" — Sir Winston Churchill

Today is the 80th anniversary of D-Day. Eighty years ago, 73,000 American troops launched the greatest amphibious invasion in human history and landed in Normandy, France to liberate Europe from Nazi Germany.

By the day’s end, over 4,000 Allied troops had been killed. 2,501 Americans died, and thousands more were wounded.

For the few remaining veterans of the Second World War, today’s anniversary could also be their last.

The youngest veterans of the war are now approaching 100-years-old. Many are older. Less than one percent of the 16.4 million Americans who served are still alive. Last year, the Department of Veterans of Affairs estimated the number was fewer than 120,000. It estimates 131 die each day.

Even less is known about the number of D-Day veterans, as the Department of Defense does not track those numbers.

Just 200 Allied veterans made the journey to Normandy for this year’s ceremonies. American Airlines attempted to track down every living American veteran, and offered to fly them to Normandy. Only 68 veterans were able to travel. Delta managed to fly another 60.

One veteran, 102-year-old Robert Perischitti, passed away en route. Perischitti witnessed the now-famous raising of the American flag at Iwo Jima, and told friends he was excited about making the trip.

During the ceremonies today, French President Emmanuel Macron presented the Légion d'honneur, France’s highest military and civilian honor, to 11 American veterans. Each of them stood up from their wheelchairs, determined to stand and receive their awards. They were shaking and struggling, carrying the weight of their years with every ounce of strength they could muster. At one point, Macron even told volunteers to stop trying to keep one veteran seated. “He wants to stand,” Macron said.

It is not hard to see why these men are regarded as “The Greatest Generation.” Though the remaining few continue to live among us, these men truly belong to another era where patriotism, love of country, service, and sacrifice were celebrated—not coincidentally, all values that today seem missing from the national dialogue, culture, and country.

In the honor of those who fought and served in World War II, I spent some time today trying to piece together a brief timeline of the day’s events to imagine what the size and scale of the day, along with what it might have been like for the 18 and 19-year-old boys who embarked on The Great Crusade.

D-Day: How it happened

Hours before the invasion began, on the eve of June 5, General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s now-famous order was distributed to the 175,000-member force that was set to participate in the invasion.

It read:

Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force!

You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle-hardened. He will fight savagely.

But this is the year 1944! Much has happened since the Nazi triumphs of 1940-41. The United Nations have inflicted upon the Germans great defeats, in open battle, man-to-man. Our air offensive has seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our Home Fronts have given us an overwhelming superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to Victory!

I have full confidence in your courage, devotion to duty and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory!

Good luck! And let us beseech the blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.

It’s difficult to even fathom what the thousands of Americans, many of them teenagers, thought and felt as they read Eisenhower’s order.

Though Eisenhower’s order is now famous, less so were his own doubts about when to begin the operation. D-Day had already been delayed one day due to poor weather, which had not subsided by the evening of June 5. If Eisenhower decided to wait again, the operation would have been delayed by several weeks. But proceeding in the poor weather conditions was equally risky. It risked leaving the first and second wave assault stranded, should weather impede on the Allies’ ability to send reinforcements.

As journalist Saagar Enjeti noted on X today, Eisenhower gave the order based on a mere weather guess. “O.K., let’s go” he told the other Allied commanders.

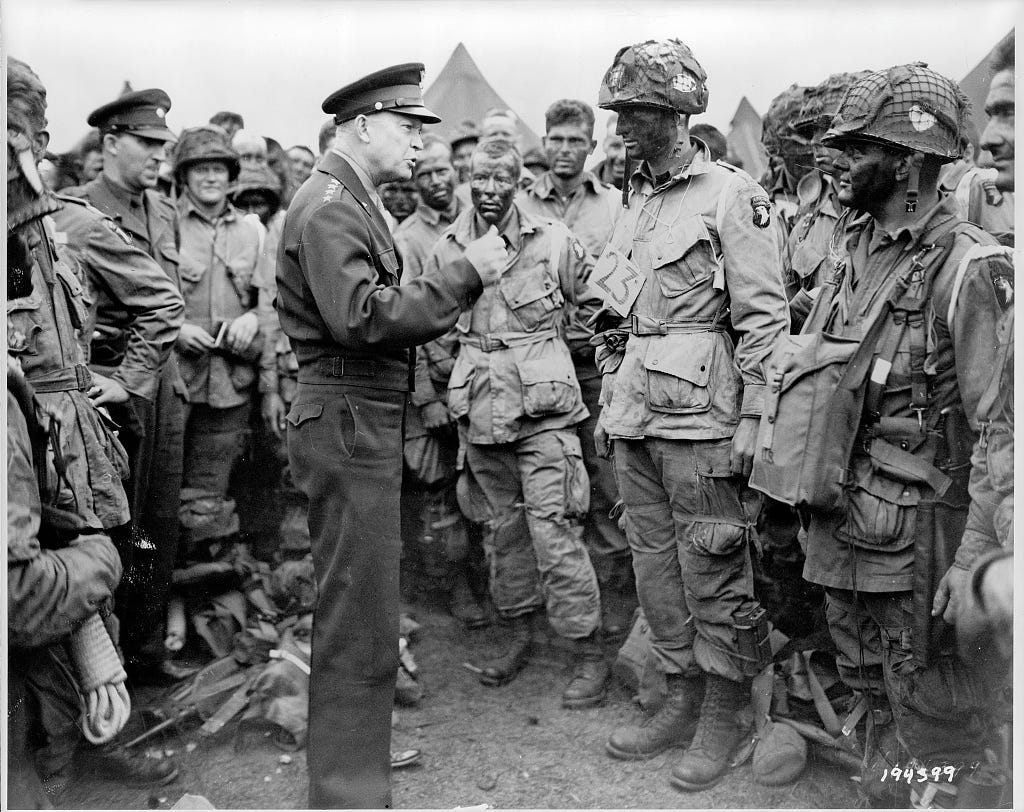

That evening, Eisenhower met with paratroopers from the 101st Airborne division. He watched as thousands loaded onto the planes to be dropped into Normandy. After watching the last plane took off towards France, a reporter said he saw tears in Eisenhower’s eyes. From Stephen Ambrose’s book, The Supreme Commander:

Then at 6 P.M. [Eisenhower] and a group of aides drove to Newbury, where the 101st Airborne was loading up for the flight to Normandy. The 101st was one of the units Leigh-Mallory feared would suffer seventy per cent casualties. Eisenhower wandered around among the men, whose blackened faces gave them a grotesque look, stepping over packs, guns, and other equipment. He chatted with them easily. The men told him not to worry, that they were ready and would take care of everything. A Texan promised him a job after the war on his cattle ranch. He stayed until all the big C-47s were off the runway.

As the last plane roared into the sky Eisenhower turned to his driver with a visible sagging in his shoulders. A reporter thought he saw tears in the Supreme Commander's eyes. He began to walk slowly toward his car. "Well," he said quietly, "it's on."

By the time Eisenhower returned to camp after midnight on June 6, the initial assault was already underway. Over 13,000 paratroopers and glider infantryman from the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions dropped into Normandy to secure strategic positions and engage the Germans. A relative of mine, my great-great uncle Private First Class James W. Walker, was among them. He would die just four days into the Battle of Normandy, fighting alongside his close friend somewhere near Sainte Mere-Eglise.

These paratrooper divisions suffered thousands of casualties. Many paratroopers were shot and killed before even landing and others drowned after landing in marshlands. Those who managed to land successfully soon realized they were dropped as far as a mile from their drop zones. The Department of Defense admits today that D-Day was “almost a failure.”

At 5 a.m., Allied ships began their bombardment of Nazi defenses along the coast, to make way for the beach landings. American forces then began landing on Utah and Omaha Beaches.

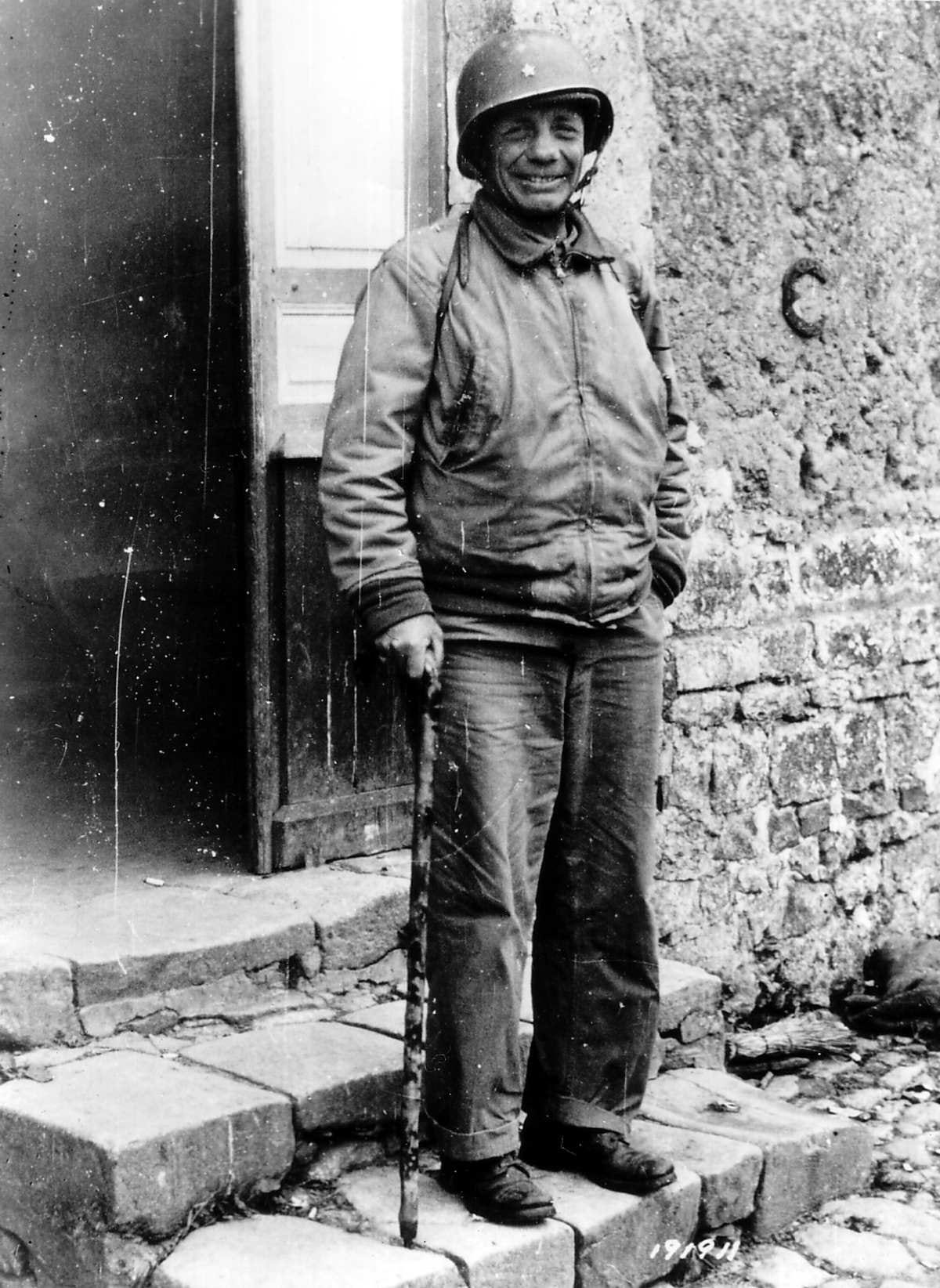

American troops first touched down on Utah Beach at 6:30 a.m. They are led by 56-year-old World War I veteran and Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. who, on three separate occasions, begged Allied commanders to let him lead the assault on Utah Beach. Roosevelt was the oldest and only general to actively participate in D-Day.

Heavy currents cause landing craft to stray 1,500 yards from their original objective. Roosevelt, reportedly one of the first men off the landing craft, declared “We’ll start the war from right here!” Armed with only a cane and a pistol, Roosevelt led American forces through heavy German fire and shelling. Between 9 and 10 a.m., American troops who landed on Utah Beach were already moving inland. By nightfall, Roosevelt had led the 4th Infantry Division six miles into France. Just 197 troops died at Utah Beach, which was the fewest amount of Allied deaths across all beaches.

Roosevelt’s heroics earned him a Medal of Honor. General Omar Bradley said Roosevelt’s actions on Utah Beach was the most heroic action he had ever seen in combat, and Roosevelt’s medal citation says he showed “valor, courage, and presence in the very front of the attack.”

He repeatedly led groups from the beach, over the seawall and established them inland. His valor, courage, and presence in the very front of the attack and his complete unconcern at being under heavy fire inspired the troops to heights of enthusiasm and self-sacrifice. Although the enemy had the beach under constant direct fire, Brigadier General Roosevelt moved from one locality to another, rallying men around him, directed and personally led them against the enemy. Under his seasoned, precise, calm, and unfaltering leadership, assault troops reduced beach strong points and rapidly moved inland with minimum casualties. He thus contributed substantially to the successful establishment of the beachhead in France.

Meanwhile on Omaha, American forces were slowed by a higher than usual tide which covered German obstacles. The obstacles prevented some landing craft from making it to shore.

Approximately three hours after the landings begin, between 8 and 9 a.m., American troops were still struggling to control the Omaha beachhead. What few troops made it out of their landing craft were soon pinned down by German machine gun fire. They were completely exposed. Allied commanders had initially planned to cover infantry with specially designed Sherman tanks that could be launched from the sea. But the tanks were deployed too early. 27 of the 29 tanks sunk before making it to shore, each trapped with their crews inside.

Yet somehow, despite the challenges, American forces managed to begin moving off the beach. Some of the remaining German troops began surrendering by midday.

By the end of D-Day, American troops only made it a mile inland from Omaha Beach. There were 2,400 casualties on Omaha Beach, which made it the bloodiest of the five beaches.

Honoring their memory

I have only met two World War II veterans. One is former Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, whose heroism left him permanently disabled in his right and left arms. The other is George Barket, who was the grandfather of a family friend.

I met Barket five years ago while he was visiting the World War II Memorial in Washington D.C. as part of an Honor Flight visit. Though I had never met him before, I quickly noticed that his mood changed when we arrived at the memorial. Being surrounded by other veterans brought him to life, but it also moved him. Barket was emotional, and brought to tears on several occasions throughout the afternoon.

“War is hell,” he told me as we sat down and took a break at a coffee stand near the Lincoln Memorial. “Don’t let them lie to you. I didn’t sleep many nights. I cried many nights,” he uttered on the verge of tears.

Later on, as we were walking near the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, a few tourists approached Barket to thank him for his service. He immediately choked up, and again repeated “we went through hell.” A man then approached Barket to shake his hand. “I was lucky, I should’ve been killed,” Barket added.

If my memory serves me right, Barket lied about his age to enlist in the Navy. According to his obituary, he was the youngest sailor on the U.S.S. Hazelwood. And, as he often reminded me that day, he fought in seven major battles including the Bombing of Okinawa, the liberation of the Philippine Islands, and the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

George Barket passed away in April 2020. He was 95.

I did not realize it then, but walking around with Barket and watching random pedestrians thank him for his service was likely the last time I will ever witness a World War II veteran honored publicly. It’s also probably the last time I will ever meet one.

Most Americans, tens of millions of them, will never know a World War II veteran. They will never meet, speak to, or personally have the opportunity to honor them.

On Fox News ahead of the anniversary of D-Day yesterday, host Martha MacCallum asked World War II veteran Ronald Scharfe his opinion on the state of the country. His response? "I feel like a foreigner in my own country lots of times, and I don't like it. It makes my heart real heavy."

I imagine Scharfe meant that ideologically, as well as literally. After hearing his response, I couldn’t help but think: in a country that is becoming increasingly multicultural and foreign-born (over 15% of the country, which is the highest number on record) how many Americans truly feel a connection to D-Day or the veterans of the Second World War? I assume fewer than ever.

I live and grew up in Miami, Florida. Though it may be an outlier compared to other cities, native-born citizens (42.2% of the population) are a minority. I suspect even fewer have ancestral ties dating back pre-WWII. Most Miami residents were born in another country. Do any of these individuals feel any sense of pride, or a connection, to American forces of the Second World War? I wouldn’t necessarily fault them if they didn’t. Why would or should they? And that’s true for such individuals across the country.

Like other wars before it, the memories and stories of World War II and its heroes will fade with time. That’s just a reality. I don’t know what the solutions are to prevent that in an ever-changing country.

But I do know this: any American who loves their country and is proud of their heritage—even if that heritage is fairly recent in this country—has a duty to remember those who served in World War II. Share their stories, honor their bravery honored, and pass their memories on.

Enjoyed reading this!

Thanks!